Suppression and Expression

Few artists and even fewer non-artists today fully appreciate the circumstances surrounding the inception of modern art, a transition from an enforced style of representational picture making to an evolved form of painted individual expression. It was a process, which broke with traditional client specified needs to become an artistic statement. Today, it might be analogous to a staff copywriter quitting to become a poet.

Only after we understand the politics, technological innovations, and changing events of the 19th century do we begin to understand why the departure was both inevitable and essential from an artistic perspective.

Photography's Invention 1807-1839

Nicéphore Niépce would invent the first internal combustion engine, then called the Pyréolophore. After leaving the engine design in the hands of his brother Claude, Niépce went on to produce the first photographic image in 1822. It was an eight-hour-long exposure process of a silver/asphalt ground he called a Heliograph. Niépce had adapted an artist's camera obscure device to create this, the earliest surviving photograph[1] and first permanent photo image, entitled View from the Window at Le Gras.

In 1829, the Parisian theatre set designer Louis Daguerre partnered with Niépce to reduce the exposure time using a plate coated with silver iodide. The resulting high contrast image with improved detail was then fixed with a standard salt solution. This greatly enhanced process became the first practical photograph, which he called the Daguerréotype process. Daguerre would further modify the artist's camera obscura device to become a more controlled exposure chamber.

Portrait of Louis-François Bertin, by the neoclassicist artist, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, was exhibited in 1833 at the Paris Salon, it became popular because of its incredible realism. Ironically, around the same time, Louis Daguerre would be perfecting the technology behind Nicéphore Niépce's initial photograph. Ingres' painting was subsequently panned by critics who declared "its naturalism vulgar and its coloring drab" [2]. By comparison, Daguerre's Daguerréotype process would become a world sensation over the next decade.

Financially ruined and under considerable stress caused by his brother Claude's funds' mismanagement of the Pyréolophore engine, Nicéphore Niépce died of a stroke in 1833 at age 68. However, six years later, in 1839, the French government acquired the camera design and process. In exchange, France provided a lifetime pension to Niépce's surviving partner, Louis Daguerre, who had perfected the results. The government of France then shared its intellectual property so it could be commercially produced.

The Camera and the Paint Tube, 1840-1850

Ironically, it would be a student of Jacques-Louis David, the iron-fisted traditionalist (and Ingres' instructor), who would manufacture the first commercially successful camera. After trying his hand as a painter, furniture maker, and conservator of fine art paintings, Alphonse Giroux would find fame and fortune constructing and selling Daguerreotype Cameras.

This early form of photography became extremely popular throughout the 1840s and 1850s, displacing all but the best portrait painters.

The camera would forever impact how a studio was employed. For centuries, artists had been using the camera obscura device. When models were unavailable for extended periods (i.e., busy clients sitting for portraits), the device would be employed to render quick but accurate outline sketches. Furthermore, as talented as artists may be, few are gifted with the ability, and many more cannot be trained to capture exact portrait likenesses. Over time, less successful artists would turn to photography for income, converting their painting workspaces into photography studios.

For historical and mythological paintings, which required several figure models, the employment of a camera became a financially prudent approach. Instead of hiring models for extended periods, the artist would do still Daguerreotype Plates of models and props to work from later. Most elaborate historical paintings and portrait paintings were commissions with deadlines, where visual accuracy wasn't just desired but was a contract requirement.

Purists today may argue with the use of photography for artistic purposes. However, artistic livelihoods at that time required perfectly accurate likenesses, which was very much the case in the neoclassical, academic world of 19the century France. Furthermore, it was common practice for one artist to paint a quick but accurate facial portrait (possibly using a camera obscura) of a famous, often busy individual (i.e., Napoleon, George Washington, etc.) and then use that rendering to create a variety of portraits later. The convenient and accurate camera replaced these time-consuming and often rushed processes.

In 1841, around the same time the camera became available, the disposable Tin Paint Tube would be invented by American artist and Boston portrait painter John Rand. The impact of this innovation should not be underestimated. It enabled greater mobility for the en plein air painting approach, employed at that time by the Barbizon School of painters.

Instead of transporting undependable animal bladders filled with paint or multiple palettes prepared in advance to a painting location, artists could simply carry convenient, fully loaded, ready-to-use tubes of paint. Rather than discarding the unused paint, it could be retained in capped tubes, unsullied and ready for use on whatever painting followed.

Again, there would be purists who would resist convenience over traditional studio-based painting and paint grinding. However, to be on location, in daylight, with the option of selecting one pure color after another, without time-consuming paint grinding, became an entirely new form of expression. Some might consider it an enriching experience, even fun. The inexpensive, portable, expendable tin paint tube made this possible. The painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir would later say, "Without paints in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism." [3]

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, or simply Talleyrand, treated Eugène Delacroix as his personal ward and influenced the dispersal of government commissions in his favor while serving as France's Prime Minister, had left office in 1815 and died in 1838. Delacroix would sometimes be the guest of Napoleon III at the Château de Compiègne, but that was the extent of their relationship.

However, regarding the arts, Louis-Napoléon's tastes were antiquated and out of touch with the cultural revolution underway in Europe. His favorite painters were Alexandre Cabanel and Franz Xaver Winterhalter, both darlings of the Salon's heyday.

Cabanel's work was reminiscent of a neoclassical style of the 19th century's first decade. In contrast, Winterhalter's work was embellished to the extreme and reminiscent of earlier Rococo styling, popular with the deposed Bourbon king, Louis XVI.

By 1844, Delacroix had retired to private life. Dealing with health issues, he spent much of his time in a small cottage in Champrosay. Nevertheless, in response to the Second Empire's expressed conservatism and feeling the need for greater artistic unity and freedom, he along with romantic sculptors Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse and Aimé Millet, painter Puvis de Chavannes, and writer Théophile Gautier formed the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862. It was what curator/historian Hans-Ulrich Simon referred to as a Secessionist manifestation.[4]

The Société would become a declaration of expressed independence from neoclassicism and academia regarding the future of art while directly challenging the Paris Salon's control over French art.

Dissension and Re-education 1852-1862

The Salon garnished its name from the Salon Carré, where the first exhibition was held. By 1725, the exhibit was moved to the Louvre Palace and became known as the Salon de Paris (Paris Salon). Presentation at the Salon was essential for any artist who wished to secure a prosperous future as a painter or sculptor in France. Moreover, because of ongoing government support, an exhibition at the Salon was also considered a mark of royal favor.

Over time, the exhibition went from semi-private to public. After the French Revolution, it became a government-sponsored event. By the 19th century, it had opened its doors to foreign artists and became the most anticipated art exhibition in the Western World.

As participation grew, exhibitions became juried to maintain a consistent venue, with the government frequently being involved with juror selection to best reflect national tastes. Consequently, with France's late entry to Romanticism and the occasional nostalgic relapse in taste, many artists, including lifelong academicians, began to complain, voice formal opposition and even protest. In response, the stoic Salon would only tighten its entry requirements.

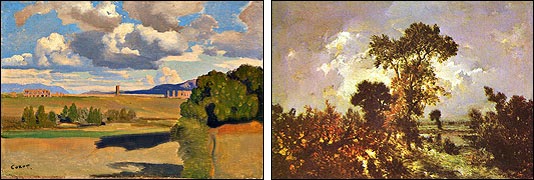

In 1829, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot came to Barbizon, France, to paint in the forest of Fontainebleau, a location occasionally visited by fellow artist Théodore Rousseau. Corot's approach to painting was greatly admired by Delacroix, who stated: "...ideas come, and he adds them while working; it's the right approach" [5]. Delacroix's description could be applied to all the artists who came to embrace this open-air approach to painting.

Rousseau would take up residence in the forest village in 1848. He would then be united with fellow artists Jean-François Millet and Jules Dupré, who had also taken up painting in the forest community. They, in turn, would be joined by Charles-François Daubigny, who had joined the Barbizon School in 1843.

Daubigny would befriend Camille Corot in 1852 and fall under the influence of Gustave Courbet later that same year. Courbet's involvement in politics approached fanaticism and would eventually lead him to drink, poor health, and early death.

John Constable and JMW Turner would gradually introduce Romanticism to France's traditional world of neoclassical academia.

Their works would impress a new generation of French painters with their brilliant vision and unconventional application of paint. For example, the Impressionist Claude Monet would later pay close attention to Turner's paint application techniques.

During the Paris Salon exhibit of 1824, the Salon jury was impressed enough with Constable's painting The Hay Wain to award it the gold medal. Traditional in subject matter and composition, the painting was an open book of articulated detail, achieved through the non-traditional technique of alla prima, impasto paint application. Delacroix, Corot, and Rousseau were amongst those who were favorably impressed by the painting.

Another instructor of non-traditional painting techniques was Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1802-1897). Also a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, de Boisbaudran had a somewhat novel approach to instructing paint appreciation. He would have his students go to the Louvre and study painting by the old masters to memorize the paintings and their paint application techniques. He would then have his students return to class and attempt to rapidly copy the paintings from memory. Fantin Latour, Auguste Rodin, and Alphonse Legros were amongst his students.

Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre (1806-1874) retired to private life in his Paris studio after producing several successful historical paintings. Despite being an expatriate Swiss national, Gleyre was keen on French politics and a voracious reader of political journals. Like Gustave Courbet, he maintained politically active views throughout his career.

After Louis Philippe I replaced Charles X, the Bourbon king, Gleyre would use his studio for regular political gatherings where he and like-minded individuals espoused their liberal and often radical views. In 1842, he took over the studio of artist Paul Delaroche, where Gleyre then taught several younger artists direct paint application technique and, above all, work ethic. Never did he accept payment from his students. Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler were amongst his students.

Consequently, some traditional artists, both accomplished and student, began to experiment and voice reservations over the Salon's control of painting style through restrictive entry guidelines. In time, award practices and the granting of government commissions would come under fire as well.

In 1849, Gustave Courbet's painting After Dinner at Ornans earned him the gold medal at the Paris Salon, which meant he no longer required jury approval to exhibit. However, in 1855 a surprised Courbet had two major works, The Painter's Studio and A Burial at Ornans, rejected from the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) by Napoleon III's Superintended of the Imperial Museums, Émilien de Nieuwerkerke. Neuwerkerke then changed the approval clause for gold medal winners at the Salon, and Courbet was henceforth barred from exhibiting there.

After being rejected from the Exposition Universelle, Courbet decided to strike back. He erected a provisional structure next door to the exposition site, which he then named The Pavilion of Realism, to display his works.

Courbet then decided to write his Realist Manifesto as the introduction to his independent personal exhibit. In it, he insists he no longer wishes to "imitate" the work of others, "ancient" or "modern," and that "art for art's sake[6] is too trivial a role". Instead, Courbet wished to employ the "consciousness of my (his) own individuality" to paint the "customs," "ideas," and "appearances of my (his) own time." In short, Courbet wished not to continue a tradition of idealized renderings and instead paint only what he knew, which was the people of that day.

When French Realism is used, its definition should not be confused with any visual rendering style, like photo-realism or hyperrealism, but is instead intended to describe a cultural realism of present-day events (real-life, not photo-real). For Courbet, that would mean the ordinary working class. For the Barbizon painter Jean-François Millet, it would be the rural working class. For painter and printmaker Honoré Daumier, it would be the urban working class and government figures. All of these individual efforts were deliberate instances of rebellion against the cultural traditions imposed by the Salon and its government-sponsored exhibits, which favored idealized renderings of history, mythology, or embellished portraiture.

Courbet's The Pavilion of Realism managed to get the attention of the cultural officials and artists. They were already discontent with the government's enforcement of sanctioned art via the Salon and other government-sponsored events. Consequently, it would mark the beginning of rebellious, independent exhibits.

Cultural War - 1863

Émilien de Nieuwerkerke was a French citizen of Dutch descent and occasional sculptor who rose through the ranks via marriage and love affairs. Most notable was his relationship with Mathilde Bonaparte, cousin of Napoleon III. Under Napoleon III, Nieuwerkerke became a pseudo-minister of culture with a wide range of control over the French art world. The Emperor named him Superintended of the Imperial Museums, including the Louvre, Luxembourg, Versailles, and Saint-Germain-en-Laye collections.

In 1853, Nieuwerkerk became a free member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Aside from his museum posts and Academy roll, he was also the Intendant or personal manager of the imperial household, its holdings, and priceless objets d'art.

Nieuwerkerk exerted considerable control over artwork approved for state-supported exhibitions, beginning with the Exposition Universelle in 1855. In that instance, Nieuwerkerk approved a request to have the work of William Wyld, an English painter, hung in the French section while rejecting two significant works by French artist Gustav Courbet. Clearly, having some connection to Nieuwerkerk held considerably more weight than a Salon gold medal.

In 1863, Nieuwerkerke (by then the Comte de Nieuwerkerke) decided, over the fierce opposition of its members, to reform the École des Beaux-Arts. Like Napoleon III, his tastes in art were nostalgic to the point of being antiquated, so much so, the Count was attacked by both liberal and conservative elements within the art community. Nevertheless, he created the Chair of Art History to mandate art education, infused with highly conservative, if not dated, views [7][8].

Nieuwerkerke's my-way-or-highway ministerial approach proceeded with the weight of the imperial government behind him, which he employed to exert considerable control over the appearance of suppression of artwork by contemporary artists, the presentation of awards, and the issuance of government commissions.

However, by 1863 the Salon was under the direct influence of Napoleon III's Second Empire and its reigning lord of government taste, the Comte de Nieuwerkerke. He was by then serving as the Salon's jury chair. In line with the École des Beaux-Arts reforms of the same year, Nieuwerkerke's Salon jury had tightened entry requirements to a point where two-thirds of all submitted works were eliminated from entry, the most significant number of rejections in the Salon's history. In addition, only traditional, realistic paintings executed with academic painting techniques of the long-established genre (which by then were considered dated) were allowed admission.

The two most famous paintings in the 1863 Salon exhibition were Alexandre Cabanel's The Birth of Venus and Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry's The Pearl and the Wave. In describing The Pearl and the Wave, art historian Bailey van Hook's review of the work accurately reflects the imperial taste of that time: "...the subject woman is shown lying down sluggishly for the gratification of the looker-on who she describes as "voyeuristic viewer" [8]. Similarly, French art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary comments, "a Parisian modiste...lying in wait for a millionaire gone astray in his wild spot." [9]

Nevertheless, the works represented a tradition dating back to before Jacques-Louis David's historical paintings, which depict women as objects, almost props, smaller and weaker than men. These 1863 Salon works would seem to hark back to the Rococo period and painter François Boucher's depictions of sensuous nudes as objects of desire.

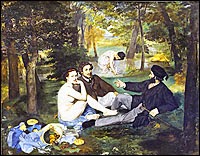

Ironically, Édouard Manet's painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) would be rejected for its scandalous rendering of a nude female air-drying after bathing, while sitting amongst two fully clothed men. In the background, a partially clothed woman bathes, seemingly oblivious to any passersby.

Journalist Émile Zola defended Le déjeuner, writing: "this belief is a gross error, for in the Louvre there are more than fifty paintings in which are found mixes of persons clothed and nude" [10]. Undoubtedly, Zola enjoyed the irony of connecting the Nieuwerkerke jury's decision to works in the same museum under his care.

What is most striking about Manet's piece is the deliberate pose held by the woman as she stares at the viewer. This is quite different from Cabanel's fictitious Venus, who is apparently unaware and very much the opposite of Baundry's female figure, who desires any viewer's gaze. Perhaps the nude subject's direct stare put the jury off? In any event, Nieuwerkerke's handpicked jury would have objected to the straightforward, alla-prima painting style, wherein the deliberately visible brushstrokes were much in conflict with traditional academic techniques of the day.

Whistler's Symphony in White No. 1, The White Girl became the other celebrated reject of the 1863 Salon exhibit. It remains unclear today for the painting's rejection from the Salon. It was rejected a year earlier in London by the conservative Royal Academy, and that in itself may have been enough.

The painting was a portrait of Whistler's mistress, Joanna Hiffernan. She would later model for Courbet, though being a mistress would not have been that uncommon and certainly not grounds for rejection.

One thing Nieuwerkerke's stacked jury would have found objectionable about Whistler's Symphony was, again, the non-traditional handling of the paint. The direct painting approach with clearly visible paint strokes would have had much in common with Manet's Le déjeune and would have been sufficient for its elimination.

Disgruntled artists were turning out in number to protest exclusive practices of the government-controlled Salon, the government's tampering with the arts, and excessive influence resulting from the Emperor's personal tastes. Subsequently, the Emperor released the following statement: "Numerous complaints have come to the Emperor on the subject of the works of art which were refused by the jury of the Exposition. His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry." [10]. As a result, the Salon des Refusés (Exhibition of Rejects) was held in the Palais de l'Industrie.

Journalist Émile Zola reported that members of the public pushed through those crowded galleries, and "the rooms were full of the laughter of spectators" [11]. No doubt, the government was counting on an adverse reaction since the enormous rejection included large numbers of mundane and poor artwork. However, the works of Manet, Whistler, and others managed to stand out. They were noted by the press, the public and continued to raise questions regarding excessive government control. Nevertheless, the Salon refused to change its ways until after the fall of the Second Empire and the Emperor's exile in England. After that, the Salon would regularly hold its Salon des Refusés but, by then, public interest in the Salon and the works of its traditionalists had waned.

Théophile Gautier's famous quote "l'art pour l'art" (Art for art's sake). It's the difference between making a picture and painting verse. Clearly, the invention of the camera and its accurate photograph and the freedom of movement provided by the paint tube would indeed liberate the artist from just taking pictures? For Manet and the next generation of artists, the picture would be what Zola called a "pretense to paint."

The chain had been broken. Tradition had become just that, tradition. Over the next century and a half, artistic freedom would sponsor more than a hundred art movements, some different, many similar. Instead of settling for just a picture, a painting would mimic literature and music. It would go beyond being just a picture created from a client or committee's specifications.

Few artists and even fewer non-artists today fully appreciate the circumstances surrounding the inception of modern art, a transition from an enforced style of representational picture making to an evolved form of painted individual expression. It was a process, which broke with traditional client specified needs to become an artistic statement. Today, it might be analogous to a staff copywriter quitting to become a poet.

Only after we understand the politics, technological innovations, and changing events of the 19th century do we begin to understand why the departure was both inevitable and essential from an artistic perspective.

Photography's Invention 1807-1839

Nicéphore Niépce would invent the first internal combustion engine, then called the Pyréolophore. After leaving the engine design in the hands of his brother Claude, Niépce went on to produce the first photographic image in 1822. It was an eight-hour-long exposure process of a silver/asphalt ground he called a Heliograph. Niépce had adapted an artist's camera obscure device to create this, the earliest surviving photograph[1] and first permanent photo image, entitled View from the Window at Le Gras.

In 1829, the Parisian theatre set designer Louis Daguerre partnered with Niépce to reduce the exposure time using a plate coated with silver iodide. The resulting high contrast image with improved detail was then fixed with a standard salt solution. This greatly enhanced process became the first practical photograph, which he called the Daguerréotype process. Daguerre would further modify the artist's camera obscura device to become a more controlled exposure chamber.

Portrait of Louis-François Bertin, by the neoclassicist artist, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, was exhibited in 1833 at the Paris Salon, it became popular because of its incredible realism. Ironically, around the same time, Louis Daguerre would be perfecting the technology behind Nicéphore Niépce's initial photograph. Ingres' painting was subsequently panned by critics who declared "its naturalism vulgar and its coloring drab" [2]. By comparison, Daguerre's Daguerréotype process would become a world sensation over the next decade.

Financially ruined and under considerable stress caused by his brother Claude's funds' mismanagement of the Pyréolophore engine, Nicéphore Niépce died of a stroke in 1833 at age 68. However, six years later, in 1839, the French government acquired the camera design and process. In exchange, France provided a lifetime pension to Niépce's surviving partner, Louis Daguerre, who had perfected the results. The government of France then shared its intellectual property so it could be commercially produced.

The Camera and the Paint Tube, 1840-1850

Artistic Convenience

|

| Click to enlarge The Daguerreotype Camera: Popular in the mid-19th century, one of the first successfully model was produced by Alphonse Giroux, a former student of artist Jacques- Louis David. |

This early form of photography became extremely popular throughout the 1840s and 1850s, displacing all but the best portrait painters.

The camera would forever impact how a studio was employed. For centuries, artists had been using the camera obscura device. When models were unavailable for extended periods (i.e., busy clients sitting for portraits), the device would be employed to render quick but accurate outline sketches. Furthermore, as talented as artists may be, few are gifted with the ability, and many more cannot be trained to capture exact portrait likenesses. Over time, less successful artists would turn to photography for income, converting their painting workspaces into photography studios.

For historical and mythological paintings, which required several figure models, the employment of a camera became a financially prudent approach. Instead of hiring models for extended periods, the artist would do still Daguerreotype Plates of models and props to work from later. Most elaborate historical paintings and portrait paintings were commissions with deadlines, where visual accuracy wasn't just desired but was a contract requirement.

Purists today may argue with the use of photography for artistic purposes. However, artistic livelihoods at that time required perfectly accurate likenesses, which was very much the case in the neoclassical, academic world of 19the century France. Furthermore, it was common practice for one artist to paint a quick but accurate facial portrait (possibly using a camera obscura) of a famous, often busy individual (i.e., Napoleon, George Washington, etc.) and then use that rendering to create a variety of portraits later. The convenient and accurate camera replaced these time-consuming and often rushed processes.

Artistic Portability

|

| Tubes of Paint: Renoir would later say "Without paints in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism." |

Instead of transporting undependable animal bladders filled with paint or multiple palettes prepared in advance to a painting location, artists could simply carry convenient, fully loaded, ready-to-use tubes of paint. Rather than discarding the unused paint, it could be retained in capped tubes, unsullied and ready for use on whatever painting followed.

Again, there would be purists who would resist convenience over traditional studio-based painting and paint grinding. However, to be on location, in daylight, with the option of selecting one pure color after another, without time-consuming paint grinding, became an entirely new form of expression. Some might consider it an enriching experience, even fun. The inexpensive, portable, expendable tin paint tube made this possible. The painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir would later say, "Without paints in tubes, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were later to call Impressionism." [3]

Empire Returns, 1851

Napoleon III's Coup d'etat

France's internal struggles would not end with the July Revolt of 1830 (the subject of Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People), the June Rebellion of 1832, or the Revolt of 1848. Instead, the division would begin anew with two failed coup attempts and a third successful one in 1851, all made by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, who became known as Napoleon III (Napoleon I's son, François Charles Joseph Bonaparte, had died in 1832 of Tuberculosis). Finally, playing the role of the ancient Gaius Octavian, Louis-Napoléon decided to make a claim to his uncle's former title of Emperor and again dissolve the Republic. |

However, regarding the arts, Louis-Napoléon's tastes were antiquated and out of touch with the cultural revolution underway in Europe. His favorite painters were Alexandre Cabanel and Franz Xaver Winterhalter, both darlings of the Salon's heyday.

Cabanel's work was reminiscent of a neoclassical style of the 19th century's first decade. In contrast, Winterhalter's work was embellished to the extreme and reminiscent of earlier Rococo styling, popular with the deposed Bourbon king, Louis XVI.

- Note: Regarding the artwork in the figure to the above right. The contrasting dates associated with the outmoded styles of these works are of particular interest. For example, the classically styled Birth of Venus painting was completed and purchased by the Emperor in 1863, the Impressionists' Salon des Refusés exhibition, and Delacroix's death. On the other hand, the imperial neoclassical portrait of Louis-Napoléon, standing next to crown and coronation robe, was completed in 1865, the same year Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and the late French Romantic composer Hector Berlioz was finishing his memoirs.

Confirming Independence

By 1844, Delacroix had retired to private life. Dealing with health issues, he spent much of his time in a small cottage in Champrosay. Nevertheless, in response to the Second Empire's expressed conservatism and feeling the need for greater artistic unity and freedom, he along with romantic sculptors Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse and Aimé Millet, painter Puvis de Chavannes, and writer Théophile Gautier formed the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862. It was what curator/historian Hans-Ulrich Simon referred to as a Secessionist manifestation.[4]The Société would become a declaration of expressed independence from neoclassicism and academia regarding the future of art while directly challenging the Paris Salon's control over French art.

Dissension and Re-education 1852-1862

The Paris Salon and Gauged Control

The Paris Salon began in 1674 as the official exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts de Paris, a division of the artistic study at the Institut de France. The exhibition's initial purpose was to display the works of graduate students of the École des Beaux-Arts.The Salon garnished its name from the Salon Carré, where the first exhibition was held. By 1725, the exhibit was moved to the Louvre Palace and became known as the Salon de Paris (Paris Salon). Presentation at the Salon was essential for any artist who wished to secure a prosperous future as a painter or sculptor in France. Moreover, because of ongoing government support, an exhibition at the Salon was also considered a mark of royal favor.

Over time, the exhibition went from semi-private to public. After the French Revolution, it became a government-sponsored event. By the 19th century, it had opened its doors to foreign artists and became the most anticipated art exhibition in the Western World.

As participation grew, exhibitions became juried to maintain a consistent venue, with the government frequently being involved with juror selection to best reflect national tastes. Consequently, with France's late entry to Romanticism and the occasional nostalgic relapse in taste, many artists, including lifelong academicians, began to complain, voice formal opposition and even protest. In response, the stoic Salon would only tighten its entry requirements.

The Barbizon School and Seeds of Change

As early as the 1820s, Parisian artists were increasingly aware of the Romantic Art movement already in vogue beyond France's borders. By then, the direct paint application techniques and passionate visions of other European artists were making a lasting impression.In 1829, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot came to Barbizon, France, to paint in the forest of Fontainebleau, a location occasionally visited by fellow artist Théodore Rousseau. Corot's approach to painting was greatly admired by Delacroix, who stated: "...ideas come, and he adds them while working; it's the right approach" [5]. Delacroix's description could be applied to all the artists who came to embrace this open-air approach to painting.

Rousseau would take up residence in the forest village in 1848. He would then be united with fellow artists Jean-François Millet and Jules Dupré, who had also taken up painting in the forest community. They, in turn, would be joined by Charles-François Daubigny, who had joined the Barbizon School in 1843.

Daubigny would befriend Camille Corot in 1852 and fall under the influence of Gustave Courbet later that same year. Courbet's involvement in politics approached fanaticism and would eventually lead him to drink, poor health, and early death.

John Constable and JMW Turner would gradually introduce Romanticism to France's traditional world of neoclassical academia.

Their works would impress a new generation of French painters with their brilliant vision and unconventional application of paint. For example, the Impressionist Claude Monet would later pay close attention to Turner's paint application techniques.

During the Paris Salon exhibit of 1824, the Salon jury was impressed enough with Constable's painting The Hay Wain to award it the gold medal. Traditional in subject matter and composition, the painting was an open book of articulated detail, achieved through the non-traditional technique of alla prima, impasto paint application. Delacroix, Corot, and Rousseau were amongst those who were favorably impressed by the painting.

Rebel Teachers

One artist who voiced concern over France's selective art practices was Thomas Couture (1815-1879). A graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts and winner of the Prix de Rome. Couture would become one of the celebrated academicians of the 19th century. After the success of his painting Romans during the Decadence (1847), he turned to teach and opened a painting school of his own, with the hopes of producing France's most significant historical painters. However, somewhat of an aging rebel, he ignored traditional painting techniques and published his own book on paint application and practices, entitled Conversations on Art Methods. It was published in 1879, the year of his death. Édouard Manet would study under Couture from 1850 to 1856.Another instructor of non-traditional painting techniques was Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran (1802-1897). Also a graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts, de Boisbaudran had a somewhat novel approach to instructing paint appreciation. He would have his students go to the Louvre and study painting by the old masters to memorize the paintings and their paint application techniques. He would then have his students return to class and attempt to rapidly copy the paintings from memory. Fantin Latour, Auguste Rodin, and Alphonse Legros were amongst his students.

Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre (1806-1874) retired to private life in his Paris studio after producing several successful historical paintings. Despite being an expatriate Swiss national, Gleyre was keen on French politics and a voracious reader of political journals. Like Gustave Courbet, he maintained politically active views throughout his career.

After Louis Philippe I replaced Charles X, the Bourbon king, Gleyre would use his studio for regular political gatherings where he and like-minded individuals espoused their liberal and often radical views. In 1842, he took over the studio of artist Paul Delaroche, where Gleyre then taught several younger artists direct paint application technique and, above all, work ethic. Never did he accept payment from his students. Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and James Abbott McNeill Whistler were amongst his students.

Consequently, some traditional artists, both accomplished and student, began to experiment and voice reservations over the Salon's control of painting style through restrictive entry guidelines. In time, award practices and the granting of government commissions would come under fire as well.

Dirty Politics

|

| Click to enlarge Gustave Courbet's After Dinner at Ornans was a Salon gold medal winner who later had its rights and privileges withdrawn. |

After being rejected from the Exposition Universelle, Courbet decided to strike back. He erected a provisional structure next door to the exposition site, which he then named The Pavilion of Realism, to display his works.

Courbet then decided to write his Realist Manifesto as the introduction to his independent personal exhibit. In it, he insists he no longer wishes to "imitate" the work of others, "ancient" or "modern," and that "art for art's sake[6] is too trivial a role". Instead, Courbet wished to employ the "consciousness of my (his) own individuality" to paint the "customs," "ideas," and "appearances of my (his) own time." In short, Courbet wished not to continue a tradition of idealized renderings and instead paint only what he knew, which was the people of that day.

French Realism

Courbet's Realist Manifesto ran contrary to almost every principle of the French Academic tradition. Nevertheless, it was a defiant message to the Salon and Exposition Universelle juries regarding discriminatory art approval practices. Today, when one views his work, it becomes clear Courbet believed the ordinary people, free of all title and pretense, best represented the subject concept he chose to depict.When French Realism is used, its definition should not be confused with any visual rendering style, like photo-realism or hyperrealism, but is instead intended to describe a cultural realism of present-day events (real-life, not photo-real). For Courbet, that would mean the ordinary working class. For the Barbizon painter Jean-François Millet, it would be the rural working class. For painter and printmaker Honoré Daumier, it would be the urban working class and government figures. All of these individual efforts were deliberate instances of rebellion against the cultural traditions imposed by the Salon and its government-sponsored exhibits, which favored idealized renderings of history, mythology, or embellished portraiture.

Courbet's The Pavilion of Realism managed to get the attention of the cultural officials and artists. They were already discontent with the government's enforcement of sanctioned art via the Salon and other government-sponsored events. Consequently, it would mark the beginning of rebellious, independent exhibits.

Cultural War - 1863

Nieuwerkerk's Cultural Ministry

|

| Émilien de Nieuwerkerke - Superintendent of the Imperial Museums and all-around pseudo- Minister of Culture for France's Second Empire. |

In 1853, Nieuwerkerk became a free member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Aside from his museum posts and Academy roll, he was also the Intendant or personal manager of the imperial household, its holdings, and priceless objets d'art.

Nieuwerkerk exerted considerable control over artwork approved for state-supported exhibitions, beginning with the Exposition Universelle in 1855. In that instance, Nieuwerkerk approved a request to have the work of William Wyld, an English painter, hung in the French section while rejecting two significant works by French artist Gustav Courbet. Clearly, having some connection to Nieuwerkerk held considerably more weight than a Salon gold medal.

In 1863, Nieuwerkerke (by then the Comte de Nieuwerkerke) decided, over the fierce opposition of its members, to reform the École des Beaux-Arts. Like Napoleon III, his tastes in art were nostalgic to the point of being antiquated, so much so, the Count was attacked by both liberal and conservative elements within the art community. Nevertheless, he created the Chair of Art History to mandate art education, infused with highly conservative, if not dated, views [7][8].

Nieuwerkerke's my-way-or-highway ministerial approach proceeded with the weight of the imperial government behind him, which he employed to exert considerable control over the appearance of suppression of artwork by contemporary artists, the presentation of awards, and the issuance of government commissions.

Art Revival of 1863

By 1863, the annual government-sponsored Paris Salon art exhibit had become the premier showcase for art school graduates and aspiring artists. For the past two centuries, its awards, subsequent commissions, and purchases had been a springboard to many an artists' careers. Serious artists all desired their work to appear on its highly coveted walls.However, by 1863 the Salon was under the direct influence of Napoleon III's Second Empire and its reigning lord of government taste, the Comte de Nieuwerkerke. He was by then serving as the Salon's jury chair. In line with the École des Beaux-Arts reforms of the same year, Nieuwerkerke's Salon jury had tightened entry requirements to a point where two-thirds of all submitted works were eliminated from entry, the most significant number of rejections in the Salon's history. In addition, only traditional, realistic paintings executed with academic painting techniques of the long-established genre (which by then were considered dated) were allowed admission.

The two most famous paintings in the 1863 Salon exhibition were Alexandre Cabanel's The Birth of Venus and Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry's The Pearl and the Wave. In describing The Pearl and the Wave, art historian Bailey van Hook's review of the work accurately reflects the imperial taste of that time: "...the subject woman is shown lying down sluggishly for the gratification of the looker-on who she describes as "voyeuristic viewer" [8]. Similarly, French art critic Jules-Antoine Castagnary comments, "a Parisian modiste...lying in wait for a millionaire gone astray in his wild spot." [9]

Nevertheless, the works represented a tradition dating back to before Jacques-Louis David's historical paintings, which depict women as objects, almost props, smaller and weaker than men. These 1863 Salon works would seem to hark back to the Rococo period and painter François Boucher's depictions of sensuous nudes as objects of desire.

Celebrated Rejects

|

| Click to enlarge Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe - Rejected from the Paris Salon, it becomes a rallying point for the Impressionists. |

Journalist Émile Zola defended Le déjeuner, writing: "this belief is a gross error, for in the Louvre there are more than fifty paintings in which are found mixes of persons clothed and nude" [10]. Undoubtedly, Zola enjoyed the irony of connecting the Nieuwerkerke jury's decision to works in the same museum under his care.

|

| Click to enlarge Whistler's Symphony in White, No 1 Reasons for rejections were less clear than Manet's Le déjeuner |

Whistler's Symphony in White No. 1, The White Girl became the other celebrated reject of the 1863 Salon exhibit. It remains unclear today for the painting's rejection from the Salon. It was rejected a year earlier in London by the conservative Royal Academy, and that in itself may have been enough.

The painting was a portrait of Whistler's mistress, Joanna Hiffernan. She would later model for Courbet, though being a mistress would not have been that uncommon and certainly not grounds for rejection.

One thing Nieuwerkerke's stacked jury would have found objectionable about Whistler's Symphony was, again, the non-traditional handling of the paint. The direct painting approach with clearly visible paint strokes would have had much in common with Manet's Le déjeune and would have been sufficient for its elimination.

Salon des Refusés

Even before the 1863 Salon exhibition, the highly conservative Second Empire was facing criticism from the French public. Beginning in 1860, public outcry for freedom of the press was joined with outrage from France's sizeable Catholic population over the Empire's Italian policy to remove Rome from Vatican sovereignty. In addition, the economy was taking a hit due to reduced exports caused by the American Civil War. Members of the government were now protesting for a right to vote approval of a bloated imperial budget. As there was no doubt Nieuwerkerkehe and like-minded jurors were behind the massive exclusion resulting from the 1863 Salon exhibition judgment, Napoleon III's government faced considerable backlash from that large number of rejected artists. |

| Palais de l'Industrie (Palace of Industry) - Where the Salon de Paris and the Salon des Refusés was held in the year 1863. |

Journalist Émile Zola reported that members of the public pushed through those crowded galleries, and "the rooms were full of the laughter of spectators" [11]. No doubt, the government was counting on an adverse reaction since the enormous rejection included large numbers of mundane and poor artwork. However, the works of Manet, Whistler, and others managed to stand out. They were noted by the press, the public and continued to raise questions regarding excessive government control. Nevertheless, the Salon refused to change its ways until after the fall of the Second Empire and the Emperor's exile in England. After that, the Salon would regularly hold its Salon des Refusés but, by then, public interest in the Salon and the works of its traditionalists had waned.

Spokesperson Zola

Émile Zola's published article defending Manet's Le déjeuner goes on to makes a most revealing observation, one that in many ways underscores the emergence of artistic modernity. "Painters, especially Édouard Manet, who is an analytic painter, do not have this preoccupation with the subject which torments the crowd above all; the subject, for them, is merely a pretext to paint, while for the crowd, the subject alone exists." [12]The chain had been broken. Tradition had become just that, tradition. Over the next century and a half, artistic freedom would sponsor more than a hundred art movements, some different, many similar. Instead of settling for just a picture, a painting would mimic literature and music. It would go beyond being just a picture created from a client or committee's specifications.

Meanwhile, advancements in photography and the invention of motion pictures would fulfill what Zola described as the "crowd's" needs for visual accuracy, which included realistic portraits, portrayals of history, and telling stories. As for the artists of 1863, the door had finally been opened. Soon, the Impressionists would run towards its streaming light to paint its poetry.

ISBN-13: 978-1454900023, pp. 2-3

2. Tinterow, Gary; Conisbee, Philip; Naef, Hans (1999). Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,

ISBN 0-8109-6536-4, p. 503

3. Renoir, Jean - Renoir - My Father, (1894, Boston: Little Brown 1962, Columbus Books Ltd. 1988, New York Review Books Classics, 2001),

ISBN 978-0-940322-77-6, p. 69

4. Simon, Hans-Ulrich, Sezessionismus. Kunstgewerbe in literarischer und bildender Kunst, Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1976,

ISBN 3-476-00289-6

5. Tinterow, Gary, Michael Pantazzi, Vincent Pomarède, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1996), Corot. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art,

ISBN 0870997696, p. 150

6. Gautier, Théophile, l'art pour l'art (Art for art's sake), L’Artiste, 1855-56.

7. Mansfield, Elizabeth, Art History and Its Institutions: The Nineteenth Century, Routledge, 2002,

ISBN-13: 978-0415228695, pp. 86-88

8. Laborde, On de, Academies of Art: Past and Present, New York, NY, Da Capo Press, 1973, pp 249-51; and Boeme, The Teaching Reforms of 1863, pp. 4-6

9. Shaw, Jennifer L. Art History, Vol. 14, The Figure of Venus: Rhetoric of the Ideal and the Salon of 1863, Association of Art Historians, 1991

ISSN: 0141-6790, No. 4

10. Published in Le Moniteur on 24 April 1863. Cited in Maneglier, Hervé, Paris Impérial - La vie quotidienne sous le Second Empire, p. 173

11. Meneglier, Hervé, Paris Impérial- la vie quotidienne sous le Second Empire, Éditions Armand Colin, (1990). p. 173.

12. Zola, Émile, Édouard Manet - Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1867, et lps 91

What's this thing called "Fine Art"? The portable camera and the Industrial Revolution changed the art world forever. Today similar seeds are being sewn for yet another departure.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Romanticism and Modern Thought: include key movements that continue to have lasting impact since the Industrial Revolution and Impressionism. Modern Art is just a few clicks away.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Art Capitalized: Passions and innovations in painting techniques begin to impact the conservative world of neoclassical art as artists begin to question tradition.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

tmallon

References

1. Gustavson, Todd, The Camera: A History of Photography from Daguerreotype to Digital, Sep 4, 2012, Sterling Signature; Reprint edition (September 4, 2012),ISBN-13: 978-1454900023, pp. 2-3

2. Tinterow, Gary; Conisbee, Philip; Naef, Hans (1999). Portraits by Ingres: Image of an Epoch. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,

ISBN 0-8109-6536-4, p. 503

3. Renoir, Jean - Renoir - My Father, (1894, Boston: Little Brown 1962, Columbus Books Ltd. 1988, New York Review Books Classics, 2001),

ISBN 978-0-940322-77-6, p. 69

4. Simon, Hans-Ulrich, Sezessionismus. Kunstgewerbe in literarischer und bildender Kunst, Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1976,

ISBN 3-476-00289-6

5. Tinterow, Gary, Michael Pantazzi, Vincent Pomarède, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1996), Corot. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art,

ISBN 0870997696, p. 150

6. Gautier, Théophile, l'art pour l'art (Art for art's sake), L’Artiste, 1855-56.

7. Mansfield, Elizabeth, Art History and Its Institutions: The Nineteenth Century, Routledge, 2002,

ISBN-13: 978-0415228695, pp. 86-88

8. Laborde, On de, Academies of Art: Past and Present, New York, NY, Da Capo Press, 1973, pp 249-51; and Boeme, The Teaching Reforms of 1863, pp. 4-6

9. Shaw, Jennifer L. Art History, Vol. 14, The Figure of Venus: Rhetoric of the Ideal and the Salon of 1863, Association of Art Historians, 1991

ISSN: 0141-6790, No. 4

10. Published in Le Moniteur on 24 April 1863. Cited in Maneglier, Hervé, Paris Impérial - La vie quotidienne sous le Second Empire, p. 173

11. Meneglier, Hervé, Paris Impérial- la vie quotidienne sous le Second Empire, Éditions Armand Colin, (1990). p. 173.

12. Zola, Émile, Édouard Manet - Le déjeuner sur l'herbe, 1867, et lps 91

What's this thing called "Fine Art"? The portable camera and the Industrial Revolution changed the art world forever. Today similar seeds are being sewn for yet another departure.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Romanticism and Modern Thought: include key movements that continue to have lasting impact since the Industrial Revolution and Impressionism. Modern Art is just a few clicks away.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE

Art Capitalized: Passions and innovations in painting techniques begin to impact the conservative world of neoclassical art as artists begin to question tradition.

Visit this later update by CLICKING HERE